| Name | Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) |

| Administered | Federal and state |

| Federal agency | US Department of Agriculture – FNS |

| Enacted in | 1964 |

| Purpose | Helps people afford food |

| Participation | 44.3 million (March 2016) |

| Eligibility | Generally 130% FPL gross income and 100% FPL net income; $2,250 asset limit |

| Structure | Monthly cash-like payments on EBT (debit) cards |

| Funding category | Mandatory, open-ended |

| Cost | $74 billion (FY15) |

The Matter at Hand

Few programs face the scrutiny that SNAP endures. This year, hundreds of thousands of people were removed from the benefit after a provision to suspend work requirements for able-bodied adults without dependents ended. Calls to cut SNAP, often cloaked under nebulous justifications about fraud and abuse, are constant. Perversely, it’s only the fact that the benefit functions as a major subsidy to big grocers and agricultural producers that the program continues without block granting. That doesn’t mean SNAP participation isn’t highly stigmatized, or that the program won’t be gutted in the future. After all, the 2016 Republican Platform called to separate SNAP from the Farm Bill and take it away from the Department of Agriculture in order to gut the program.

The left’s demand for SNAP should be, on one hand, expansion of access by increasing income limits and disregards and streamlining application processes. On the other, we must call for a blanket increase in benefits to meet actual dietary and budget needs, including pegging a minimum benefit to inflation. Finally, we must fight against attempts to discipline the poor by, for instance, limiting SNAP purchases to foods deemed “healthy” in an undemocratic process. The requirements for retailers to accept SNAP should be made contingent not on the size and diversity of inventory a store carries, but rather upon how how that retailer treats its workers.

Participation

In March 2016, 44.3 million people received SNAP benefits, 1.3 million fewer than received benefits in March 2015. The latest participation data is available from FRAC.

In FY14, 43.6 percent of SNAP households contained children, and over half of these were in a single-adult household; 19 percent had an elderly member (note that ‘elderly’ is defined as 60 or older by SNAP), most of which were a single elderly person living alone; and 20.4 percent contained a non-elderly individual with a disability.

Participation rates are generally around 85 to 90 percent. Most groups have high participation, except for the elderly, of whom only 41 percent of eligibles are enrolled. Estimates of state-level participation range from nearly 100 percent in Maine, Oregon, Michigan, and the District of Columbia to 63 percent in California and 56 percent in Wyoming. California’s low participation rate is particularly alarming (especially considering elderly participation is only about 20 percent) given the large size of the state.

Applying for the Benefit

SNAP has a standard $2,250 asset limit regardless of household size (or $3,250 if a household member is elderly or disabled), but states can raise or eliminate this if they so choose. Sixteen states retain asset limits for SNAP.

Income requirements in most states are 130 percent of gross income and 100 percent of net income, though states have the option to set these higher if they wish. They must then use their own funds, rather than federal funds, to make up the difference.

Calculations to determine net income are somewhat complicated, relying on a number of deductions that may or may not be standard in a given state or for a particular group. Taken from the USDA website:

- A 20 percent deduction from earned income (i.e. wages, not Social Security);

- A standard deduction of $155 for households sizes of 1 to 3 people and $168 for a household size of 4 (higher for some larger households);

- A dependent care deduction when needed for work, training, or education;

- Medical expenses for elderly or disabled members that are more than $35 for the month if they are not paid by insurance or someone else;

- Legally owed child support payments;

- Some States allow homeless households a set amount ($143) for shelter costs; and

- Excess shelter costs that are more than half of the household’s income after the other deductions. Allowable costs include the cost of fuel to heat and cook with, electricity, water, the basic fee for one telephone, rent or mortgage payments and taxes on the home. (Some States allow a set amount for utility costs – called a Standard Utility Allowance – instead of actual costs.) The amount of the shelter deduction cannot be more than $504 unless one person in the household is elderly or disabled. (The limit is higher in Alaska, Hawaii and Guam.)

Depending on state and applicant circumstance, SNAP beneficiaries may be required to update their status (re-certify) monthly, quarterly, semi-annually, or annually. Since 1996, so-called ABAWDs (able-bodied adults without dependents; non-disabled 18 to 49 year olds without dependents) may only receive SNAP for three months in three years, at which point they must meet work requirements. This requirement was waived for many states since 2008; it was reinstituted in 2016, causing 500,000 people to lose SNAP benefits.

In some states, households can be made categorically eligible for SNAP because they receive brochures about their qualification for TANF. In certain states, LIHEAP receipt also grants a higher SNAP benefit (‘heat and eat’), but the level required for this was raised from $1 to $20 of LIHEAP per month as of the newest Farm Bill. Eleven states and DC kicked in extra LIHEAP funds to maintain this option.

SNAP eligibility determinations are required to be made within thirty days of application; states get dinged if they don’t accomplish this. Most applications require an interview (certain waivers allow for states to waive interviews for groups such as the elderly). There is no standard protocol, at least federally, for interviews. While the intention of the interview is twofold, to ensure people are maximizing their benefit and to ensure they have documentation necessary to make a determination, there is little preventing a caseworker from using the interview as an opportunity to, for instance, judge their clients.

I’ve also heard rumors that there’s a perverse incentive at play, and overburdened caseworkers will deny applications that may be borderline or require a great deal of documentation (such as older applicants seeking a medical expense deduction) in order to keep below the 30 day rule. Applicants have the right to an administrative hearing for appeal, but many are not aware of this.

On striking and SNAP (USDA): “Households with a person who is on strike because of a labor dispute are not eligible unless they were eligible the day before the strike and continue to be eligible at the time of application. Eligible households cannot get more SNAP benefits just because the striking member is getting less income.”

State Options

States have a number of policy options to either expand access or erect barriers to SNAP enrollment. Wisconsin included a provision to drug test applicants in its state budget; the federal government declared it illegal; Republican Members of Congress reacted by trying to pass a bill to make it legal. I’ve also heard rumors that the online screening tools for at least one state misstate a potential applicant’s eligibility (always saying that the potential applicant is ineligible).

On the other hand, states can implement online systems for applications and administration (sometimes this goes poorly), streamline applications or combine them with applications for other programs (usually TANF and Medicaid), and have a number of waiver options. Because each state has discretion over program administration, application quality and length differs wildly. Some applications may be up to 40 pages long. Virginia, for instance, recently went from a horribly formatted, garbage application to this (as well as adding the ability to apply online).

Each year, USDA FNS publishes a report on the various waivers and options that states can implement. Mathematica has analyzed these options and how well they work.

Benefit Structure

The average monthly benefit was $125.26 per person in March 2016. The minimum benefit for households two or fewer household members is $16 per month; there is no statutory minimum for larger households. (There are, in fact, people who are “eligible” for SNAP but receive $0 in benefits.) States may choose to set a higher minimum benefit, using state funds to cover the difference; at this time the District of Columbia is the only state to implement such a policy.

For a long time, I assumed SNAP was ‘cash-like.’ In other words, for a hypothetical household with a monthly income of $1,000 and a SNAP benefit of $100, the increase in ‘real’ income from SNAP of 10% would correspond to an increase in household expenditures on food of around 10%, as the SNAP benefits just replaced existing spending and freed up ‘unrestricted’ market income to be used on other household needs such as rent. However, recent research from USDA suggests this is not actually the case. Rather, 53 cents of every dollar in SNAP benefits is used on food, rather than the 5 to 10 cents suggested by the ‘cash-like’ assumption. In other words, SNAP substantially increases household spending on food (and only food at home). In addition to an insight into how the program works, it also suggests that SNAP’s structure gives it an important role in fighting hunger. (It also provides an insight into how hungry poorer Americans are.)

While the paper vouchers that gave the Food Stamp Program its former name were the norm for decades, nowadays benefits are delivered at the beginning of each month and payments made via an EBT card, which function like debit cards for federal benefits including SNAP and TANF (in some states the benefit is stored on the card, in other states the card acts as a go-between with the state agency). These debit cards are administered almost entirely by large financial institutions. Each state issues a different EBT card. The design of the card itself can be stigmatizing if it makes it clear that the person using it is a welfare recipient; some states have less obvious cards than others.

A pile of state EBT cards. Some states manage to avoid stigmatizing designs, others stumble right into them whether purposefully or not.

Benefits can be used at grocery stores, smaller convenience stores, and at many farmers’ markets (some of which have policies to double SNAP dollars). In Arizona, Michigan, and some California counties, elderly, disabled, and homeless people can use SNAP at restaurants. In addition to groceries, SNAP benefits can be used to purchase seeds. Note that stores require a certain amount and variety of inventory to qualify as a SNAP retailer, per USDA regulations.

Since SNAP money can only be spent on groceries (i.e. not prepared foods, alcohol, or tobacco), it serves as not only a welfare subsidy that helps people eat but a subsidy for industrial agriculture and grocery stores. The only public data we have on where SNAP dollars are spent, released by Massachusetts by mistake during a FOIA request in the mid-2000s, suggests that big box stores such as Walmart are the beneficiaries of a great deal of SNAP spending, which is not particularly surprising. Very probably SNAP owes its continued survival – or at least lack of block granting – to the fact that it is reauthorized in the Farm Bills which are passed every five years.

Purchases with SNAP are not taxed.

Effects

SNAP lifted 4.7 million people out of poverty in 2014, including 2.1 million children. SNAP has a significant positive effect on household food security, arguably a better measure of privation than the poverty level. The effect was particularly noticeable in participating households with children.

SNAP has a small but significant positive effect on dietary quality. Maternal receipt of SNAP during pregnancy reduces the incidence of low birth-weight by between 5 and 23 percent. SNAP participation in childhood has a significant positive lifecycle effect, resulting in significant positive effects in health, educational outcomes in early and late childhood and as an adult.

SNAP spending functions as a strong macroeconomic stimulus. USDA finds: “An increase of $1 billion in SNAP expenditures is estimated to increase economic activity (GDP) by $1.79 billion. In other words, every $5 in new SNAP benefits generates as much as $9 of economic activity.”

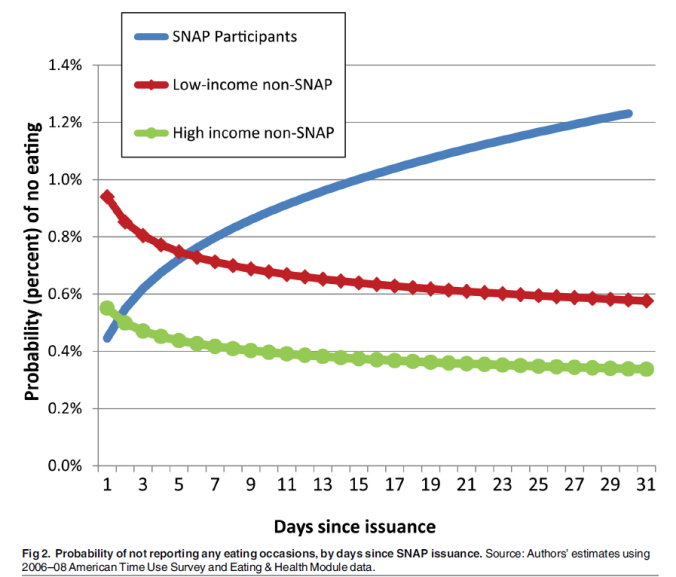

Because SNAP benefits are paid at the beginning of each month, SNAP participants are, relative to others, much more likely to skip meals later in the month; on average, they are over three times more likely to skip meals on the last day of the month than high-income people.

Other Notes

The name change from Food Stamps to SNAP occurred in 2008. Some advocates suggest it’s been successful in decreasing stigma; I’m skeptical. Running from stigma, rather than actively trying to fight it, may fool some people for a little bit, but it won’t help in the long run. The stigmatization arises largely from attitudes about poor people and racism, not the name of the program.

An ongoing debate is whether the government should be able to restrict purchases beyond what it already does (i.e. alcohol, prepared foods, etc.) to include only foods deemed healthy. Not only is this restrictive, it can actually have the opposite effect. In other words, this functions as nothing but a way of punishing the poor. Note that, despite Wisconsin’s best attempts, the federal government does not allow states leeway to restrict SNAP purchases; such directives can only come from Congress.

Trafficking rates are about 1 percent. The linked study acknowledges that “trafficking does not increase costs to the Federal Government.” Most program fraud is committed by retailers. Some is committed by state employees.

There is a temporary SNAP program called Disaster SNAP or D-SNAP for those affected by national emergencies. For D-SNAP, households use a simplified application and benefits are issued within 72 hours. Households not normally eligible for SNAP may qualify for D-SNAP as a result of disaster-related expenses. D-SNAP recipients are eligible for emergency food assistance, as well.

In an effort to avoid having to subject the troops to the “shame” of being on SNAP, the Department of Defense has a program that has all the same qualification guidelines as SNAP but is Definitely Not SNAP. Rather, it is the Family Subsistence Supplemental Allowance (FSSA) program. FSSA does differ from SNAP in one notable way however, in that it puts benefits directly into a paycheck. In a way, it serves a similar purpose as a child benefit does in other countries, since the only way a soldier could qualify is with non-working dependents in the household, albeit only for active-duty military personnel. The program is very small; in 2015 only 188 active-duty servicemembers were enrolled. Beginning FY 2017, the program will no longer be available to those stationed in the continental United States. DOD estimates that some 20,000 active-duty military personnel use SNAP, but these numbers are fraught because they utilize American Community Survey data, in which SNAP usage is a household variable. The estimate of 20,000 is so low that it could be entirely due to noise. (For instance, a SNAP household respondent placing a child in the survey who is active-duty military but does not actually live in the household would, with weights, appear as several thousand people in the survey, none of whom exist in real life.)